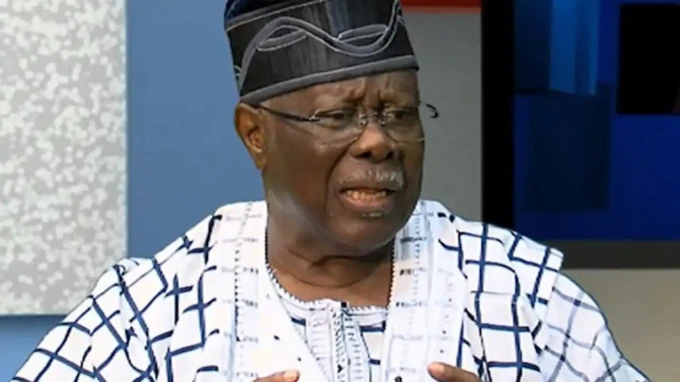

The Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) has issued a scathing rebuke of Bauchi, Katsina, Kano, and Kebbi States’ decision to shutter all public and private schools during Ramadan, labeling it a grave threat to education, equity, and national cohesion. In a statement released on Sunday from Abuja, CAN President Archbishop Daniel Okoh decried the move as shortsighted and exclusionary, warning that the five-week closures—spanning late February to early April 2025—risk deepening the region’s already dire out-of-school children crisis and fracturing Nigeria’s pluralistic fabric.

CAN’s alarm is rooted in stark realities. “Bauchi, Katsina, Kano, and Kebbi already face alarming rates of out-of-school children, averaging 44%, far above the national average,” Okoh stated, citing National Bureau of Statistics data. Bauchi tops the list at 54%, followed by Kebbi (45%), Katsina (38%), and Kano (35%)—a collective 10 points higher than the national 34%. The closures, he argued, will disrupt academic calendars and exacerbate this “critical issue,” undermining Nigeria’s push for universal education. “Education is a fundamental right and the foundation of societal progress,” CAN stressed, a right now imperiled by what it calls an excessive policy.

The directive’s unilateral nature fuels CAN’s ire. Okoh criticized the lack of consultation with CAN leaders, school owners, parents, and civil society in the affected states. “Policies affecting diverse populations—Muslims, Christians, and others—must be the result of inclusive dialogue,” he asserted. The absence of such engagement, he warned, “erodes trust and unity in our pluralistic society.” Private school owners, particularly Christians, echo this sentiment, arguing that a diverse student body shouldn’t be uniformly denied education for a religious observance not all share.

CAN juxtaposed Nigeria’s approach with Islamic-majority nations like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, where schools remain open during Ramadan with adjusted schedules. “If Islamic heartlands can maintain a balance between education and religious observance, Nigeria’s northern states should follow suit,” Okoh contended. The five-week shutdown—Bauchi’s from February 26 to April 5, per SaharaReporters, and similar spans in Katsina, Kano, and Kebbi—lacks global precedent, CAN argued, branding it disproportionate and avoidable.

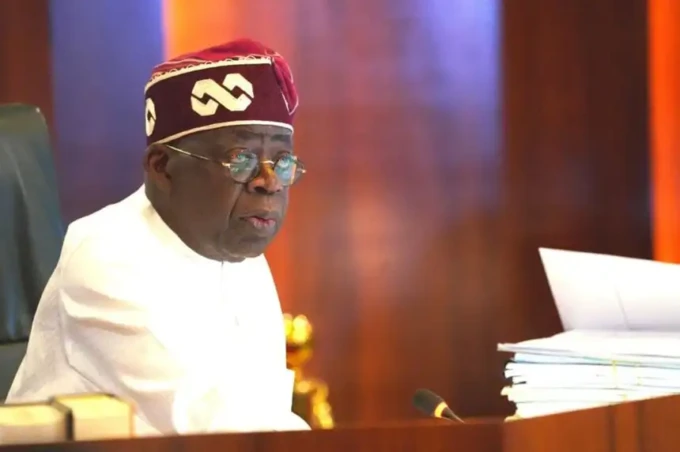

The stakes escalated with reports of enforcement. In Katsina, the Hisbah Board’s February 27 circular mandated private school closures, threatening repercussions for noncompliance. In Kano, Hisbah arrested youths for not fasting, signaling a broader clampdown. CAN sees this as overreach, urging Governors Bala Mohammed (Bauchi), Dikko Umar Radda (Katsina), Abba Kabir Yusuf (Kano), and Nasir Idris (Kebbi) to rethink their stance through dialogue. “We are prepared to seek restraining orders through the courts,” Okoh warned, signaling legal action if the closures persist, to safeguard constitutional rights to education and freedom of conscience.

The academic fallout is already clear. Bauchi’s official calendar split the 2024/2025 second term into two phases—January 5 to February 28, then April 6 to 29—with a five-week Ramadan break in between. This truncation, CAN contends, sacrifices learning for millions. Private schools, serving mixed faiths, feel particularly aggrieved, their operations upended by a policy they had no hand in shaping. “The rights of students and families who do not observe Ramadan must be respected,” CAN insisted, framing it as a fairness issue.

CAN’s plea is both a critique and a call to action. “Let us build a Nigeria where faith and progress harmonize, where no child’s education is sacrificed,” Okoh concluded, urging peace while pressing for policy reversal. The 44% out-of-school rate looms as a damning backdrop—each closed classroom risks nudging it higher. The governors face a choice: double down or dial back, with education and unity hanging in the balance.

This clash isn’t just regional—it’s national, spotlighting how religious priorities intersect with secular rights. As CAN braces for a fight, legal or otherwise, Nigeria watches a debate unfold that could redefine governance in its diverse north. For now, four states stand firm, but the echoes of shuttered schools may yet force a reckoning.

This article is biased. Ramadan closures are a cultural tradition, not a threat. Education can adapt. Lets promote unity!

I disagree, respecting religious holidays is important for diversity and inclusivity in education. Lets promote unity through understanding.

Can we truly prioritize unity over religious freedom in school closures for Ramadan? Its a complex issue.

Isnt it unfair to prioritize religious holidays over education? Schools closures for Ramadan can disrupt learning for all students.