Comprising five of Nigeria’s 36 states, south-east Nigeria is a region marked by a persistent and resilient atrocity. Between mid-2015 and the end of 2023, Nigeria Mourns, a monitoring coalition, documented approximately 3,000 killings in this zone based on open-source records. However, unofficial estimates suggest the true toll could be far higher—potentially five uncounted deaths for every one recorded. The violence has intensified since 2019, with Anambra State bearing the brunt of this deadly surge. Far from a recent phenomenon tied to the 2017 proscription of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), this crisis traces its roots back over 25 years, roughly to the 1998 assassination of Igwe Amobi IV of Ogidi in Enugu.

The Heidelberg Institute’s annual Conflict Barometer identifies south-east Nigeria as one of eight significant conflicts in the country, labeling it a “violent crisis of secession.” It ranks alongside the Middle Belt’s armed pastoralism crisis, surpasses the Niger Delta’s resource militancy, and trails only the Boko Haram insurgency and north-western banditry in severity. Yet, the popular narratives framing this crisis—secession, “unknown gunmen,” and a kinetic response—oversimplify a complex reality, obscuring root causes and perpetuating an interminable tragedy.

The secession narrative, often linked to IPOB, is seductive for its emotional and financial appeal. It stokes a unifying resentment among Nigerians against a perceived “Igbo question” while justifying lucrative military deployments under the guise of national integrity. However, this framing falters under scrutiny. In hotspots like Awkuzu, home to Nigeria’s most notorious police station, extrajudicial killings of detainees number in the hundreds. In Obosi and Awka, inter-cult and gang warfare claim countless young lives. Ogbaru sees organized gangs orchestrate sophisticated hydrocarbon theft, while Lokpanta, a lawless borderland, thrives as a hub for kidnapping and liquidation. These realities defy the secessionist trope and suggest a deeper crisis of crime and governance, not a coherent separatist agenda.

The second narrative, that of “unknown gunmen,” is a longstanding Nigerian myth, dating back to the 1977 attack on Fela Anikulapo-Kuti’s Kalakuta Republic, blamed on an “unknown soldier.” In the south-east, this label has persisted—seen in the 2011 disappearance of Ihembosi’s traditional ruler and the 2014 abduction of former Anambra Commissioner Chike Okoli. Rather than indicating mysterious actors, it reflects state incapacity and indifference to impunity. The “unknown” perpetrator is less a perpetrator’s identity and more a symbol of public despair—a loss of faith in accountability.

The third framing, a predominantly kinetic response, assumes Nigeria can shoot its way out of this mire. This is a delusion. The south-east’s crisis demands precision—a scalpel, not a hammer. Over 2022–2024, I co-led the Truth, Justice and Peace Commission (TJPC) with Bianca Ojukwu, consulting victims, security forces, clergy, politicians, and militias. Our findings revealed two truths: this is fundamentally a governance crisis, rooted in a lack of trust in political legitimacy, and there’s a widespread yearning for community recovery and healing.

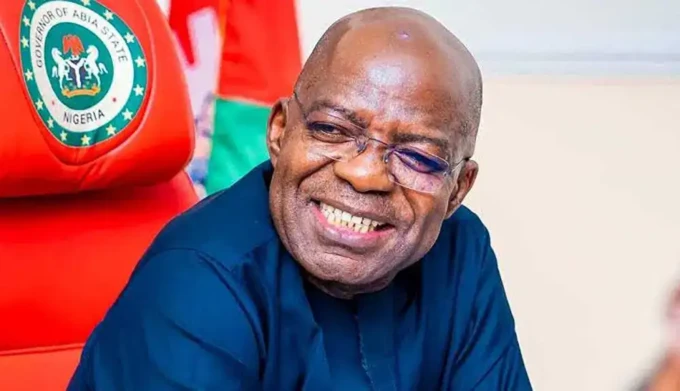

The interplay of perpetrators and security forces often forms a perverse joint enterprise, both profiting from sustained instability. Enter Anambra’s Governor Chukwuma Charles Soludo, whose 2025 Homeland Security Law offers a bold counterpoint. Establishing “Agun’echemba” (sentinel at the gate) and the “Udo g’Achi” (peace shall reign) initiative, it targets atrocity insecurity head-on. Section 18, addressing “transactional ritualism,” has sparked debate for allegedly lacking clarity and targeting traditional worship. Yet, TJPC consultations with Juju priests revealed their support for rooting out ritualists enabling violence, suggesting regulation over repression.

The law also confronts leadership deficits. As The New Humanitarian noted in 2005, rigged elections breed disenchantment, a trend persisting since 2003. Illegitimate leaders, compromised by their origins, often exacerbate violence rather than resolve it. Soludo’s approach bucks this trend, emphasizing accountable governance. Critically, it seeks to rebuild criminal justice—restoring trust in police, empowering magistrates, and funding prosecutors. In a region where summary killings are glamorized, this shift is revolutionary but fraught with resistance from those vested in the status quo.

South-east Nigeria’s crisis is no monolith. It’s a tapestry of crime, impunity, and misgovernance, woven over decades. Soludo’s law isn’t a panacea, but it’s a model—adaptable by other states—that dares to unravel the oversimplified secession narrative. It deserves support, for only through such audacity can the region reclaim peace from resilient atrocity.

Leave a comment